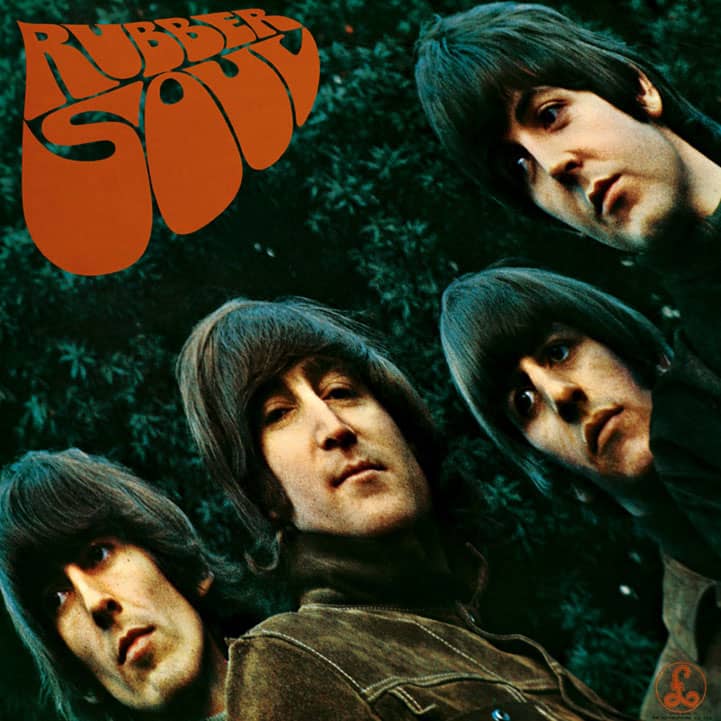

Run For Your Life is a song written by John Lennon that appears on the Rubber Soul album. On the surface it is a catchy song with a very slight country flavour, beautiful guitar parts and harmonies, entirely in keeping with the rest of this excellent album. The crisp sound was innovative and plainly influential, especially on the Monkees’ Last Train to Clarksville. Lennon later reported that it was one of George’s favourites but that that he himself had always hated it. My own ratings still largely reflect my initial superficial impressions, but it’s fair to say that the song has a much darker side that is hard to completely overlook as an adult, and harder still when one knows a bit more about Lennon’s character. While its disturbingly misogynistic lyrics are not intended to be taken literally, their menacing tone is being normalized, even celebrated:

Well, I’d rather see you dead, little girl

Than to be with another man

You better keep your head, little girl

Or I won’t know where I amYou better run for your life if you can, little girl

Hide your head in the sand, little girl

Catch you with another man

That’s the end, little girlWell, you know that I’m a wicked guy

And I was born with a jealous mind

And I can’t spend my whole life

Trying just to make you toe the lineLet this be a sermon

I mean everything I’ve said

Baby, I’m determined

And I’d rather see you dead

The song with which The Beatles began the Rubber Soul sessions, John Lennon’s ‘Run For Your Life’ was based around a line from an Elvis Presley song.

Continue reading on Beatles Bible →

Continue reading on Beatles Bible →Although this type of content was not uncommon in the 1950s and 60s (indeed the “rather see you dead” line is a direct quote of an Elvis song – Baby Let’s Play House), Run For Your Life is troubling because we now know that Lennon really was jealous and controlling in his relationships, and was at least occasionally violent towards women.

His first wife, Cynthia, suffered his possessive behaviour and aggressive outbursts most keenly in the early phase of their relationship (later he mellowed somewhat but then became neglectful and sometimes callous toward Cynthia and the couple’s son Julian):

John’s temper could be frightening and at times I felt torn to pieces by him. All sense of reason disappeared and his tantrums were awesome: he would batter away at me verbally until I gave in, overwhelmed by the force of his determination.

He was jealous of my close friendship with Phyl and even of my work, if I chose to spend an evening catching up with it instead of with him.

He was incredibly jealous of any boy who came near me and wouldn’t hesitate to warn them off. Not long after we got together we went to a party at another student’s flat. There was plenty of loud music, beer and cider, and we were having a good time until a very tall student I recognised from the sculpture department came over and asked me to dance. Before I could answer all hell broke loose as John, in a blind fury launched himself at the guy.

I tried repeatedly to reassure him but it made no difference: John was provoked to fury if another boy paid any attention to me, however innocent.

There was an air of danger about John and he could terrify me. I lived on a knife edge. Not only was he passionately jealous but he could turn on me in an instant, belittling and berating me, shooting accusations, cutting remarks or acid wisecracks at me that left me hurt, frustrated and in tears.

One night we were at a party and John went mad when someone told him Stuart [Sutcliffe] and I were dancing together. As soon as I saw the look on John’s face we stopped and, as so often before, I reassured him that it was him I loved. He seemed to accept it. But the next day at college he followed me into the girls’ loos the the basement. When I came out he was waiting, with a dark look on his face. Before I could speak he raised his arm and hit me across the face, knocking my head into the pipes that ran down the wall behind me. Without a word he waled away, leaving me dazed, shaky and with a very sore head. I was shocked, really shocked, that John had been physically violent. I could put up with his outbursts, the jealousy and possessiveness, but violence was a step too far.

Cynthia Lennon, John, excerpts from pages 34-49

In later life Lennon recognized this as a serious failing saying:

All that ‘I used to be cruel to my woman, I beat her and kept her apart from the things that she loved’ was me. I used to be cruel to my woman, and physically… any woman. I was a hitter. I couldn’t express myself and I hit. I fought men and I hit women… I will have to be a lot older before I can face in public how I treated women as a youngster.

John Lennon, David Sheff Playboy interview, September 1980

In 1965 when Run For You Life came out, Lennon likely regarded it as a dark but ultimately insignificant relationship topic: “I’m a jealous guy, toe the line”, perhaps balancing (along with songs like Norwegian Wood and I’m Looking Through You) the unthreatening romantic pop-idol personas that had been created for the band. It was part (the start?) of an unpleasant mid 60s trend for sexist and misogynistic songs that emerged as popular music moved further away from “boy meets girl, happily ever after” themes and as a macho rock culture began to displace more androgynous teeny pop (see also e.g., in the Rolling Stones’ Under My Thumb, released the following year). But the song also reveals Lennon’s complacency about his own jealousy, possessiveness and violence, a complacency he would come to regret. Because he was murdered just a few months after the Playboy interview excerpted above, he never lived to make a public reckoning with his earlier attitudes and behaviour that he’d begun to contemplate.