Piggies is a song written by George Harrison and appearing on the White Album.

George Harrison began writing ‘Piggies’ in 1966, the same year he composed the similarly ascerbic ‘Taxman’. Although musically quite different, both songs contain social commentary about financial greed and class differences.

Continue reading on Beatles Bible →

Continue reading on Beatles Bible →For this song it is well worth reading the wikipedia article as the track turned out to have an undeserved and grisly historical significance well beyond anything the Beatles intended; it has received correspondingly more critical analysis and commentary, and it is probably not a great idea to just repeat it at length here. In outline:

- Piggies (along with a few others on the White Album) was seized on by a Californian cult as part of a twisted doctrine that led them to carry out a series of brutal murders, even writing references to Piggies’ lyrics in their victims’ blood . Truly horrific.

- Piggies is also often described as having “Orwellian” and satirical. The Orwellian influence relates to the way pigs are clearly used to refer to greedy and hypocritical people, with “bigger piggies” referring to richer, and more powerful people who are “stirring up the dirt” and making things worse.

On the first point, I don’t have too much to say as I think raking through the ashes of a mass-murderers’ mind is not relevant to the music. It is an example of the way that any huge cultural phenomenon is likely to have unintended negative effects just by virtue of the sheer number of minds it affects. As the Beatles were one of the biggest global cultural phenomena of their time – it was inevitable that their influence would extend to distorted and ultimately destructive effects, as well as the more positive, benevolent effects they intended. This is comparable to any other cultural force; Lennon famously and controversially compared the scale of the Beatles influence to Christianity, which is all about loving and forgiving and has undoubtedly done a lot of good in the world. But it has also been perverted to justify, for example, burning heretics at the stake and many other atrocities, wars and every variety of oppression; as Lennon put it: “Jesus was all right… It’s them twisting it that ruins it for me.”

The hope must be that the most powerful cultural influences produce greater good than harm. In the case of the Beatles I think that’s true, but the jury is still out with many of the pervasive cultural influences that shaped the world in the 20th century and today.

On the second point, the words of Piggies do read as somewhat Orwellian. In particular they conjure up the image of the denouement of the Animal Farm fable where, in the book:

“The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

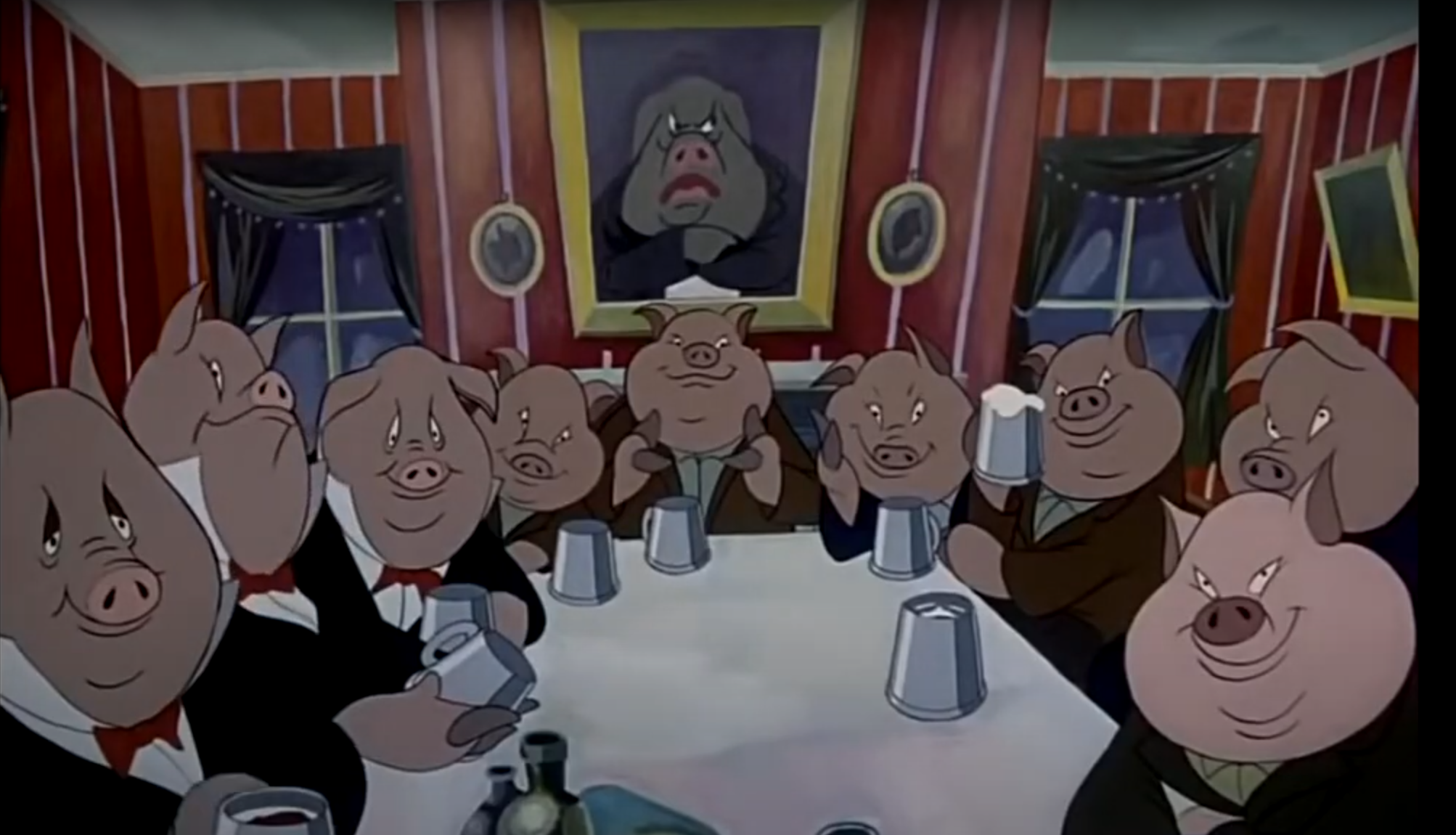

More precisely they conjure up the corresponding images from the 1954 animated movie, where the pigs are depicted wearing starched white shirts at a dinner table:

They are not actually “clutching forks and knives to eat their bacon” (a brilliant line succinctly vividly describing hypocrisy and betrayal and apparently suggested by Lennon); in the movie the hypocrisy and betrayal is shown by having the pigs literally morph into people.

It seems quite likely that Harrison was influenced by Orwell and, if so, probably by the film since he apparently also wrote a line (subsequently deleted) referring to “Pig Brother”. Pig Brother alludes to the authoritarian leader in another Orwell book, 1984, but it was coined for the movie version of Animal Farm, or rather in contemporary posters and trailers.

As a piece of music, Piggies is quite pleasant to listen to. It is well produced with baroque harpsichord played by stand-in producer Chris Thomas. It also later got a George Martin string arrangement, and the treated vocal in the middle eight is reminiscent a similar effect on Paul’s Honey Pie. All these are signs that the song was taken seriously by the band. John and Paul’s songs had received the same kind of attention on Sgt. Pepper, but George had opted out until this point.

It may have been intended as satire, but in my view, Piggies does not work as a strong example, the words are a bit too vague. Rather characteristically for Harrison’s Beatle years, it must be said, it points out a problem – identifying it with someone else – without really offering much of a solution. The words “what they need’s a damn good whacking” (actually suggested by Harrison’s mother) would have been interpreted in Britain at the time as meaning “firm discipline” rather than anything more violent, and is was likely meant as a witty reversal of the way the older generation typically regarded young people.

Zeitgeist

In 1968 as the White Album was being put together there was something of violence and revolution in the air (Revolution 1 and Revolution 9 are the Beatles more explicit response on the same album). I am speculating a bit here (and no doubt historians will have already been down this path), but it seems to have been a generational phenomenon linked to the end of World War II; there had been a huge baby boom as service personnel returned to start families at the end of the war. Those children, boomers, were the Beatles audience and they were now coming to adulthood in a world still shaped and controlled by their parents’ generation, but they were also entering adulthood earlier than previous generations, and perhaps less well prepared.

They had not experienced wartime, and in Britain and America had benefitted from an economic boom arising from the peace dividend. By their parents’ standards they had led sheltered lives, and teen culture had developed an escapist tendency (fuelled in part by psychedelic drugs); for a few months everything seemed to be cellophane flowers, tangerine skies. Good vibrations: wouldn’t it be nice?

But that level of escapism couldn’t continue. In many Western countries there was conflict over civil rights, women’s rights, the effects of capitalism and the Cold War, and many of these seem to pit the younger, progressive and optimistic generation against an older conservative one. These concerns had coalesced around a counterculture which was increasingly alienated from mainstream politics which, in turn, was increasingly seen as oppressive.

In the UK this had been a gradual process that was coming to a head in 1968 but that had its beginnings earlier, as those who had been children during the war (the Beatles contemporaries) came to adulthood through the early sixties. Satire had been a big part of the initial response. For example, That Was The Week That Was (a satirical TV show that used cutting and indirect humour to poke fun at the older generation’s politicians, leaders and class system) aired in 1962-63. It was created by Ned Sherrin (born 1931) and fronted by David Frost (born in 1939). Private Eye magazine (which used – and still uses – satire to hold powerful people to account and to ridicule) was first printed in 1961 and was founded and edited by a group of writers who were all born in the late 1930s.

In some ways, the early 60s satire boom and the Beatles (whose appeal crossed generational boundaries and tended to bring people together) had perhaps provided a safety valve and (it seems to me) the British counterculture was less defiant and angry than in other parts of the world. In other parts of the world there were more pressing reasons to rebel. For example, in the US young people were being drafted to fight in a war they largely did not believe in, and civil rights leaders and progressive young politicians had been assassinated. By 1970 protesting students at Kent State University, Ohio were being gunned down by the National Guard. In Britain young people, and their slightly older spokespeople, were being taken seriously, and some limited progress had perhaps been made to accommodate their concerns. By the time the boomers reached old age, they had lived what seems today like a charmed life, with all the benefits peacetime brought, the welfare state, the National Health Service, careers, homes, pensions and security all won by their parents’ generation, and many of them eroded since, on their watch.

Who are the Piggies today?

Khrushchev visited a pig farm and was photographed there. In the newspaper office, a discussion is underway about how to caption the picture. “Comrade Khrushchev among pigs,” “Comrade Khrushchev and pigs,” and “Pigs surround comrade Khrushchev” are all rejected as politically offensive. Finally, the editor announces his decision: “Third from left – comrade Khrushchev. (from Wikipedia)

I’m not sure if Piggies is a great example, but I do think satire, allegory and fable have the potential to be potent tools for people living under genuinely oppressive government, which seems to be on the rise lately. By saying things indirectly, the message is clearly communicated to like-minded people, but it is deniable and can’t easily be acknowledged by the powerful (since that would mean endorsing and amplifying the joke – “if the cap fits, wear it”). By bringing powerful people to ridicule, their power, which always depends to some extent on being taken seriously, is undermined. Plus, it fun! Importantly, satire can help people see that they are not alone even when it becomes difficult to openly express solidarity. It’s just a question of knowing who the bigger piggies are.